Patagonian International Marathon / Limitless Pursuits

[:en]

A Long Shot

If the Patagonian International Marathon was a movie, it would start like this:

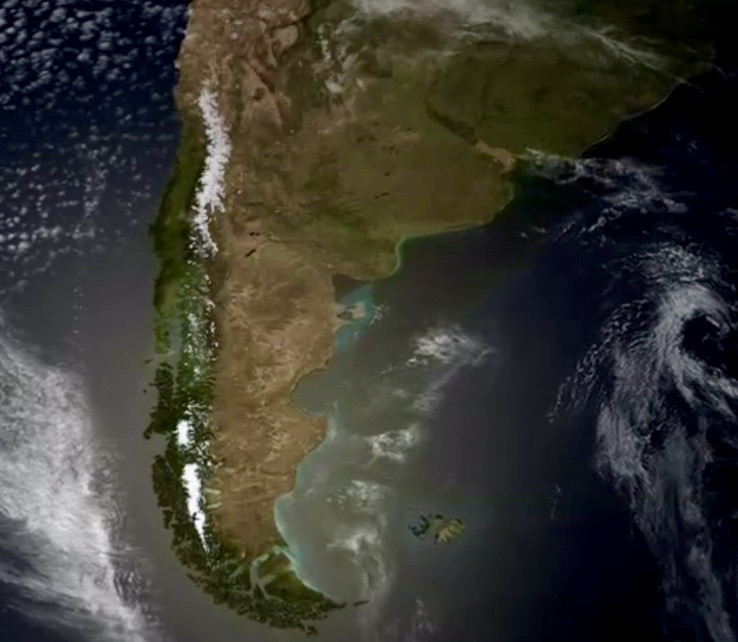

An extreme long shot of our planet, far out in space.

“Seis, Cinco, Cuatro” a Spanish voice would say and we’d zoom in, the continent of South America flaring up, the Amazon leading our eye south, the Andes spiking, the Hielo Sur ice cap draining into the furthest reaches of the land mass before the earth breaks up altogether.

“Tres, Dos, Uno” and in we would go, deeper. Between the barren windswept Land of Fire and the condor brushed peaks, a single mountain range would then fill the screen. Shards of granite would threaten to impale us as we raced towards its snow dusted peaks, and down its glaciated flanks. At it’s foot there’s a small turquoise lake. Petrified trees float up through the water with hairy-green lichen clinging to the silvery branches. On the shore, a cast of 150 brightly coloured runners are poised behind a tight tape.

I was lucky enough to be one of the extras in what happened next.

The backstory

The Patagonian International Marathon is now in its fourth year. It has been developed by the same Chilean organisation that in 2001 created the Patagonia Expedition Race; once described by National Geographic as “The Last Wild Race.” Their goal is to raise awareness of this remote region, providing runners with inspiring memories and photos that keep them connected and concerned with its pristine preservation for a lifetime.

The PIM – despite its extreme location – starts just 100m above sea level, and, allowing for the dizzying crags overhead – follows gravel roads that wouldn’t trouble a road runner. The event now offers a 10km race, a 21km half marathon (the most popular), a 42km full marathon and a 63km ultra distance event. International stars such as Ryan Sandes and Matt Flaherty have glittered the start lines in previous years – but this time, in the absence of a male lead – I decided to try and fill those running shoes myself.

The author soaks up his 30 seconds of fame at the 8th Natural Wonder of the World

30 Seconds of Fame

I was running in the 21km race – “saving myself” for the more challenging 50km Ultra Trail Torres del Paine the following week (read at Limitless Pursuits soon!) With the 10km race starting further up the road and sharing the same finish line, I estimated I could run 16km before I encountered anyone. The park guards had closed all roads to cars. If I could run then at the front, I would be alone for an hour at the end of the planet – running my closed gate tour of the Torres del Paine park – the 8th Natural Wonder of the World.

Or so the plan went….

A Year in one Day

To arrive here at 51degrees south you will most likely transfer from Santiago; Chile’s capital city. It’s a four hour flight and is the equivalent of travelling from London to Morocco, or New York to Mexico City – and then you’ve still only travelled half the length of this immense leviathan of a country that stakes its claim on this rugged terrain between the Andes and Pacific Ocean.

The PIM is held in “The Province of Last Hope,” in the deep south of Patagonia. This was the very last part of the planet to be colonised by migrating man as he travelled down the Americas after crossing the Bering Strait. Today there is still a definite frontier feeling to the climate and geography; one of unhewn roughness and unpredictability. The weather is known to present all the fluctuating conditions of an entire year, all in the same day. It’s the stomping ground for winds that push you flat, and the forging grounds for mountaineers who can still seek first ascents. The world’s largest network of fiords are found here, and glaciers march brazenly down to them at sea level, avalanching spectacularly into their frigid waters. And yet, despite this feeling that time is in a spin and there is too much to see – the very worst mistake you can make in Patagonia is to move too fast – as the locals say here, “Those who hurry in Patagonia, lose time.”

Patagonia Time

I’d set off too fast. That was painfully clear at the top of the first climb: the lactic acid working its way into my quadriceps like a caustic burn; my breath rasping out like a sawmill. The effort had buried me and I’d experienced nothing of that magic time I’d imagined alone at the front of the pack. Two runners came up behind me, clocked me for the imposter that I was, and quickly took control of the race… My private screening of the natural world’s 8th most coveted attraction, gatecrashed.

The PIM’s rolling course weaved on through hills of glacial moraine, past wind sculpted trees and turquoise lakes – the road just kissing their stoney shores as we passed. The last of the morning cloud was rising, and slowly I slipped out of the desperate rush in which I’d started the race. The air was warm now. The muscles in my face relaxed; the desperate concentration dissipating as I started to look beyond the gravel I’d been pounding.

The other runners had already moved out of sight, and I was alone again. Scuttling along the rugged road. A blip in the Patagonian wilderness, a flash in its unfathomable history. Breathing in. Breathing out. To my left, the Cuernos del Paine pushed 8,000’ out of lake Nordenskjöld – the great horns of rock jostling for geological prominence, rutting imperceptibly across ice ages. Their black granite tips, capsules of eroded time. The rock gouged in millenniums past, now lying sediment across ocean floors.

Close Up

The last few kms to the finish line sent us powering down a hillside on a step gravel road. You don’t go to Patagonia to run a PB (the 21k is seven times as hilly as the entire London Marathon) but as I cashed in on the climbs and lengthened my stride downhill – I could see 2nd place ahead and tried my best to reel him in. I was passing lots of the 10km competitors. They were clearly exhausted by the mind bending scenery and had a sort of loping, head-twisted, affectation of running as they tried to juggle forward momentum with the sensory overload that Torres del Paine weighed them down with. I exchanged high fives and was greeted in a dizzying array of languages as I chased after my man in red.

Close to the finish line I passed alongside him. “Matt” he said “ I remember you from the start line!” And I was impressed. It had been only 85 minutes, but as we ran through the land that time forgot, it had felt far longer.

The finishing gantry perched atop a grassy flat buff of rock, overlooking a wide U-Shaped valley below. A pack of guanaco had wandered over earlier on. The music had been turned off so as not to startle them, and now they were nibbling peacefully nearby. I bounced unsteadily onto the uneven surface of the thin landing strip; my footsteps muted suddenly by the soft ground. Perhaps my ears had not yet popped from the descent, but I was very aware of how silent the photographers and spectators were: respectful perhaps of the experience we were coming down from, or in awe themselves at the Torres del Paine monoliths behind us, swirling yet steadfast in the mist.

[:]

Los calcetines son mucho más caros que lo que estoy acostumbrado a pagar, pero me estoy dando cuenta que los calcetines son igual de importantes que los otros elementos técnicos de un corredor de larga distancia. Pueden hacer un diferencia importante en tu entrenamiento y tu carrera.

Los calcetines son mucho más caros que lo que estoy acostumbrado a pagar, pero me estoy dando cuenta que los calcetines son igual de importantes que los otros elementos técnicos de un corredor de larga distancia. Pueden hacer un diferencia importante en tu entrenamiento y tu carrera.

Many thanks to Pablo Garrido and his tremendous team. Many thanks also to Matias Bull from Tail Chile for keeping everyone informed during the race and to Max Keith for taking such mind bending photos. Race directors: you need these boys at your races!

Many thanks to Pablo Garrido and his tremendous team. Many thanks also to Matias Bull from Tail Chile for keeping everyone informed during the race and to Max Keith for taking such mind bending photos. Race directors: you need these boys at your races!