The contentment of the long distance runner / Ultra

Read the text only version below

I first discovered long distance running whilst working at a difficult school in northern England. The borstal-like institution was a brick and glass new-build on the top of an exposed and windy hill. The kids weren’t sent there because they had done anything wrong. They just grew up in the wrong postcode and had no other choice.

Everyday the high-grilled gate rolled back and the children trickled in with a truancy-officer tailgate. For the next seven hours I was to pump them with Steinbeck, George and Lennie, The American Dream and the old Strive and Achieve. Occasionally they listened suspiciously – a snatched hiatus between Monster energy drink breakfast, plans for the evening and under-desk sales of pilfered aftershave and perfume.

Two summers came and went. It was the longest time I’d spent working in one place. Longest time I’d done anything. Here was a time in life when you could release the brakes. Five, ten years might slip past. Sometimes you would feel like you were making a difference. But at the end of each day the kids would drift away again, back down the hill.

Autumn came hard and cold in the second year. The light was quickly sucked out of any evening escapes to rock climb in the Peak District. Instead I would listen to hammering Daft Punk on repeat as I penned through graffitied exercise books. On the day we read how Lennie killed Curley’s wife, there was a big red smudge across the afternoon sky. Later that week a child left an upturned drawing pin on my teacher’s chair. Creativity seemed dead. Simple-minded Lennie soon took his bullet.

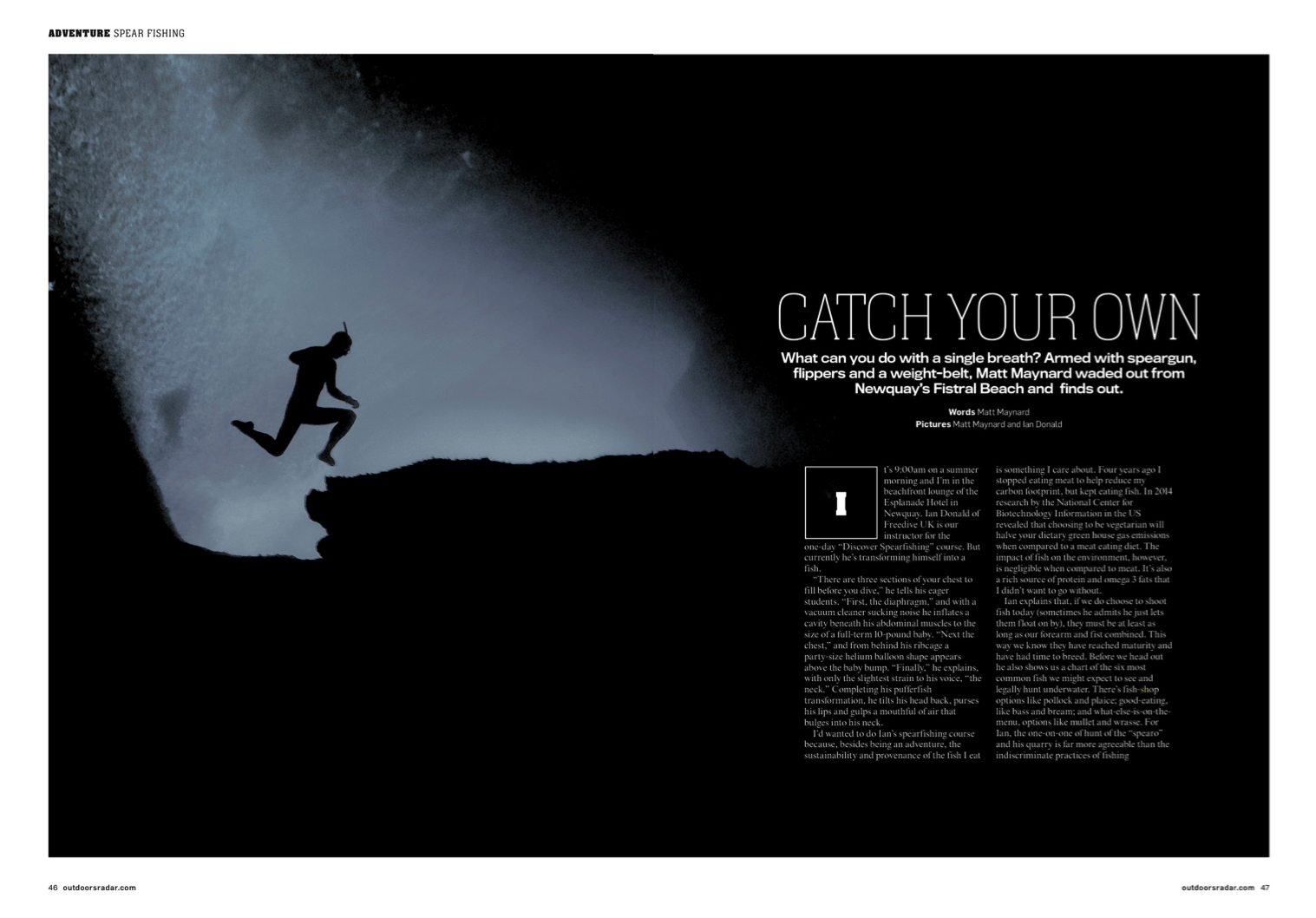

The city contracted that winter. I wasn’t sleeping much anymore. When I did sleep, time jumped forward and the high-grilled gate would be rolling back almost immediately. So instead I would stay awake, my mind raging on the last seven hours I’d spent on the hill. Occasionally on a school night an acquaintance would invite me to a party. Drinking didn’t work though and I would excuse myself early – only to go home and pace the landing. Slowly during those claustrophobic evenings, a feeling grew that I needed to get out. Out into the night. Out into the hardening knot of frozen earth on the city limits and beyond. This was the time I began to run.

I lived at this time as the lone lodger in a spacious family townhouse. I occupied half of a hot attic, whilst the other room was taken by a heavy-sleeping two-month old baby. It must have been after nine on the first night that I decided to run because my floor-mate was already asleep. Out on the frosty streets I turned the opposite direction from my daily commute to the hill, running towards the Peak District.

It was darkness I needed. A private quietness. The dampening of light and the sharpening of thought. After 30minutes of gentle uphill running, I approached the entrance to the national park and the end of the suburbs. Street lights disappeared with the abruptness of a lone candle blown out.

In the darkness, gentler senses take over. I ran past a long rustling line of leaves. I ran past startled damp horse. I ran into rising wind until high above the city. Entanglements of mind began to be unpicked. An order was found as if waking from deep sleep.

And yet, if you do go into the night to examine a disquieted mind, there is another kind of darkness that you could also expect to find. As I turned and headed back, I began to recognise the darkness I’d been feeling all that long winter on the hill. It was the darkness behind the eyes of energy drinking children. The darkness of Steinbeck’s 1920s. The darkness of high-grilled gates, shop lifted perfume, shit decisions and incompetence. Out here, looking back down on the city I lived in, there was enough space now to put a name to it. This darkness on the hill was loneliness.

Well after midnight I crept back into my room just as the baby started crying through the wall.

There were more runs after that. They weren’t always at the dead of night, but it was good to know that clarity and calm waited out there on the long lanes. I began to tease out this sensation of loneliness a little more, chipping away at the daily violence of words and actions encountered on the hill. So often what emerged at the end of each run was the same shrivelled kernel of loneliness. But at least now it had a name.

In the last term we changed to non-fiction. We read adventure stories – escapist uplifting stuff – penned well beyond the high-grilled gate and the limits of the northern city. Instead of zoning out to Daft Punk I now listened to Dylan before running. Mainly the angry protest stuff like “Ballad of a Thin Man,” and “Hurricane,” but also sober tracks too like “Don’t think twice, it’s all right.” It was my own time now to be travelling on.

Late that final school term, near the turn-around on one of my increasingly long runs, I thought about the drawing pin incident. I remembered the kids laughing. I remembered the blood stained paper towel in the waste bin. Yet most of all I reflected on the lone child who approached me quietly in the corridor some days later. “Did you know it was me?” he asked hopefully. That was my last long run in the northern city.

I moved around a lot over the next few years but I took running with me. I discovered that the long run was a place where I could unpack all sorts of other feelings, not just loneliness. I took my frustrations and restlessness regularly to this workbench. Here I would knock the blunt edges off noisy life – sometimes uncovering negativity that needed addressing. Sometimes revealing joy.

These days as a long distance runner, I rarely blow open any great feelings like I found during that winter in the northern city. If I return home with just a small truth about the way I’m feeling – there’s contentment in that. No great euphoria or sadness. Just a contentment in having found a way of living that feels better than standing still.

For all teachers who stick it out on hilltops

Issue 7 of Ultra magazine available now,

photo by Renato Cabral and not by me as incorrectly credited